When we set out to design the Participatory Grantmaking Initiative (PGM), our goal was simple: build a grant program that didn’t just invite feedback, but to build with the community, for the community. And in doing so, shift power. Participatory grantmaking involves engaging community members in funding decisions to ensure resources address their most pressing needs. To us, participation is not just about collecting feedback — it’s about co-creating a process that centres lived experience, is guided by those most impacted, and nurtures collective power.

We aimed to create a process grounded in care, compassion, and equity — one that would help disrupt or at least side-step the usual dynamics of grantmaking and offer a more relational, accessible, and humane way to resource migrant-led systems change efforts.

Through the application process, the decision-making process, and some initial feedback, we can see that we were able to achieve this in some ways, and yet there is so much more that could be done. As we move through this pilot project , we want to share what we’ve learned so far.

Read about the 16 grantees who received $500,000 of collective funding!

The application response we received

As we’ve shared before in our reflections on the design of the grant, during the application phase our focus was on creating a low-barrier process — opening the grant to registered and unregistered groups and individuals, and providing application support. Our team provided individualized application support to nearly 80 prospective applicants, in addition to hosting two webinars and weekly drop-in hours.

We ultimately received 142 applications, totalling $6.65M in needed funds, when we only had $500,000 to disburse.While we expected strong interest in the grant, this exceeded our expectations. We do not take this number and its meaning lightly – that it represents not only the hopes and ideas of many different people and communities, but also the immense pressure and challenges that individuals, groups, and organizations working for migrant justice are facing in the current socio-political climate. Applications came from across British Columbia and reflected a wide cross section of needs and visions within racialized migrant communities.

We aimed to create a process grounded in care, compassion, and equity — one that would help disrupt or at least side-step the usual dynamics of grantmaking

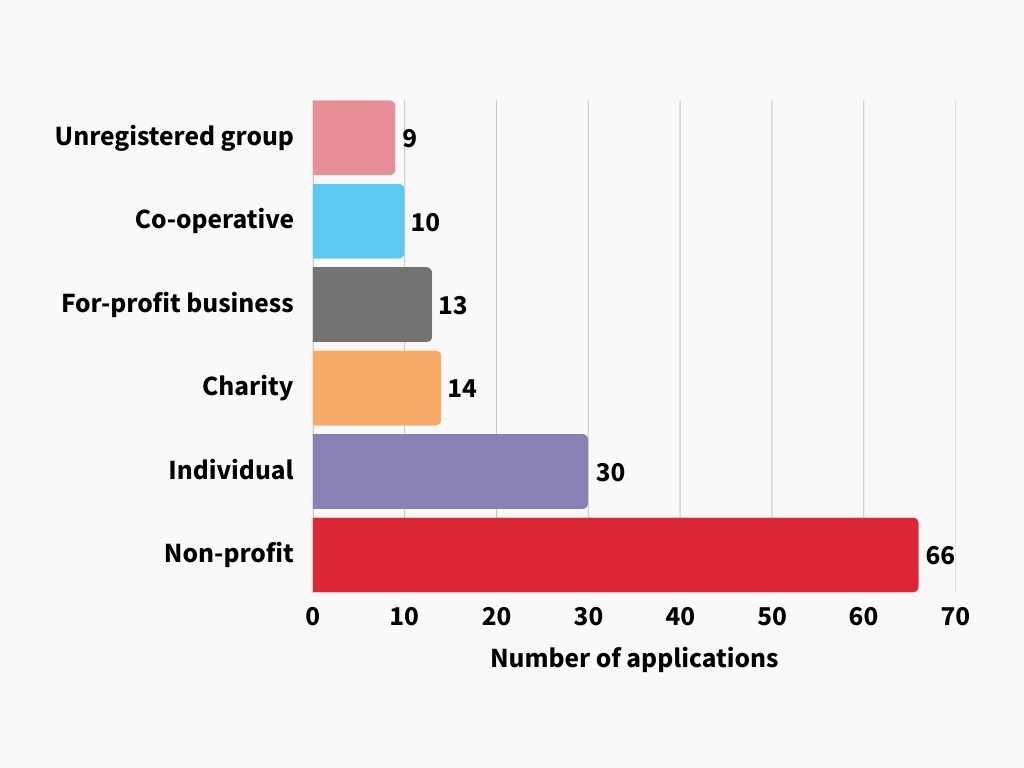

Types of organizations applying

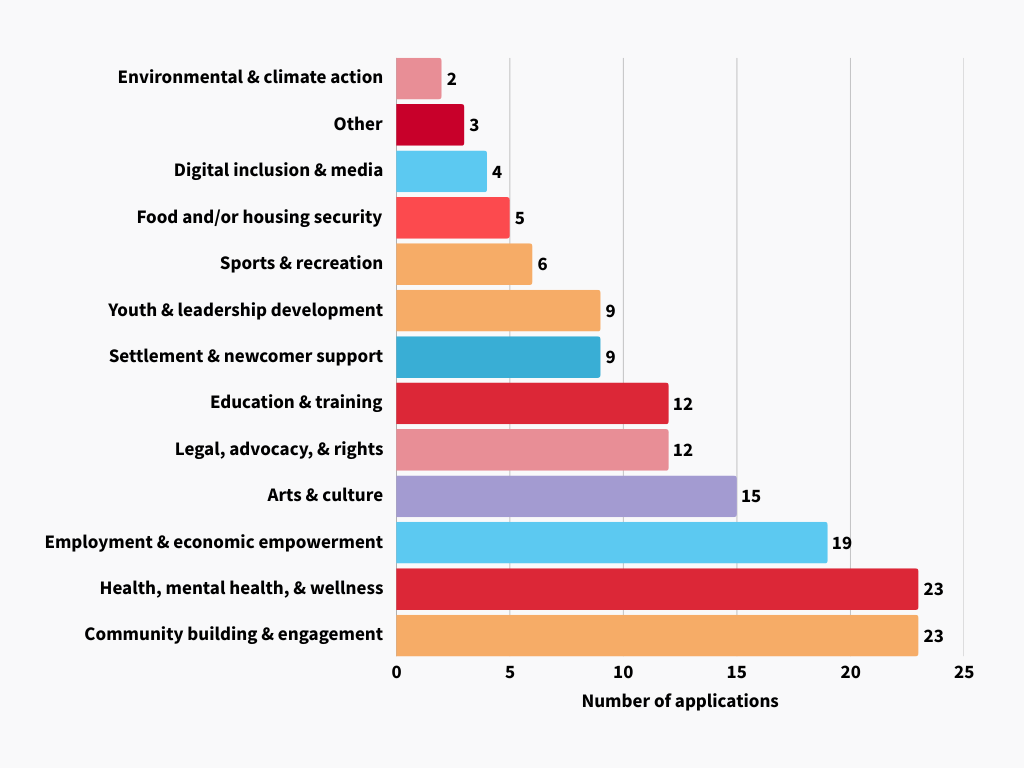

Areas of focus of the applications

How we approached the decision-making process

We had set up a decision-making group in advance to review the applications. This group included community members who helped design the grant program as well as the decision-making process itself. Soon we realized that due to the amount of applications received, the time and compensation we allocated for the decision-making group would not be enough. This challenged us to allocate more resources to decision-making to establish a process that would provide a thorough and fair review, while ensuring the community members that were making the decisions did not over-extend their capacity.

The process was designed in three main stages:

Stage 1: Two staff members first reviewed all 142 applications to confirm they met the very basic grant criteria. For example, the initiative needed to be BC-based and focused on issues faced by racialized migrant and refugee communities.

Stage 2: The decision-making group was then divided into pairs. Each pair reviewed a subset of eligible applications, ensuring two reviewers read every application in addition to the initial RLL team review. Reviewers used the same rubric that had been shared publicly with applicants during the application phase. Each reviewing pair surfaced a shortlist of strong applications to bring forward to the larger group for discussions.

Stage 3: Based on these discussions and the rubric assessment, the decision-making group identified a set of 32 applications to advance for further reviews. In this second review stage, every decision group member reviewed all of the 32 applications individually using the rubric and came back together for deeper discussions and final decisions.

In the various discussions, the RLL team members, who reviewed every application, helped contextualize the overall landscape of the applications for the decision-making group: regions, themes and issue areas, communities served, etc. They also brought forward considerations around equity and representation to complement the rubric. This included geographic diversity by supporting applications beyond the Lower Mainland, including a range of migrant communities from migrant workers to international students, and offering regular reminders to the group to not feel bound to only supporting registered, incorporated, or already-established organizations just because that felt more comfortable or might carry less risk.

Throughout the discussions, group members reminded one another to approach the review process with compassion:

- to give applicants the benefit of the doubt,

- to recognize that people communicate differently,

- to right-size expectations based on the amount of funding requested, and

- to focus on the heart of the work rather than just polished words.

Some tradeoffs we wrestled with during decision-making

We struggled with how to honour well-resourced organizations doing important work while prioritizing under-resourced grassroots efforts.

In making decisions, the group wrestled with balancing many factors – funding across different initiatives, regions, and communities; the size of grants awarded; and the kinds of work we were supporting.

We debated how to fairly assess certain initiatives that are emergent where impact might not be easy to understand and yet the importance of that work felt instinctive; or how to approach for-profits that proposed good work but whose primary mission might not align with systems change. We struggled with how to honour well-resourced organizations doing important work while prioritizing under-resourced grassroots efforts.

We questioned:

- What really constitutes systems change?

- How do we address cases where applicants have strong intentions but limited clarity on their plans for impact or community accountability?

- How do we ensure we are not inadvertently reinforcing existing power structures while also reflecting on the power we hold now as reviewers, or in the RADIUS team’s case, as facilitators of this grant program?

We grappled with these questions together, always returning to our co-created guiding compass and the principles that shaped this initiative. While it is difficult to share the discussions that the decision-making group had in a brief manner without losing context and complexity, we still wanted to share overarching themes.

What we saw in the applications — strengths, gaps, and reflections

The applications showed us incredible heart. We saw passionate people and groups working for migrant communities, many of whom are under-resourced and striving for change. Across many of the applications, we observed initiatives that are rooted in care, community connection, and building solidarity with different communities and groups. Many brought innovative ideas for policy advocacy, grassroots organizing, and building networks of mutual aid while embedding an intersectional lens across migration, health, climate, housing, food, organizing, and community engagement.

Across many of the applications, we observed initiatives that are rooted in care, community connection, and building solidarity with different communities and groups.

Certain gaps in application or misalignment with the focus of the grant and the rubric also emerged. Some applications lacked clarity on systems change or how power dynamics would be shifted. Others struggled to name the specific communities they aimed to engage or spoke broadly of “migrants” without recognizing intersectional identities or specific lived experiences. Often, initiatives did not clearly articulate, or they did not have processes in place regarding how they would practice community accountability beyond transparency to funders.

The decision-making group observed that many applicants were asking for the larger grant sizes, and proposing work that overlapped with existing settlement services, rather than pushing for deeper systemic shifts. Some established organizations had budgets that did not prioritize equitable pay/living hourly wage for their staff.

There were reflections from the decision-making group about how a few applications (representing a small subset of the overall applications) began to sound quite similar — in part, likely due to the use of AI writing tools. This often led to applications using broad buzzwords without clearly conveying the actual focus of the proposed work. To be clear, this isn’t a critique of using AI itself (that is another, complex topic in of itself), but rather a reflection that when applicants didn’t personalize or adapt the language, their narrative ended up sounding vague and generic. Some reviewers also mentioned how they think that some applicants may have felt unsure about their own abilities to express themselves and used language they thought we wanted to hear rather than speaking in their own voice.

As we share these reflections on gaps and misalignment in the applications, it is important to reiterate that the total requested funding we received far surpassed the total amount we were able to give out – we would have certainly funded more initiatives if we could.

Refining our approach through three key learnings

Based on some initial survey feedback received from applicants, we learned that our efforts to create an accessible process were appreciated: applicants told us they valued the flexible budgeting, the support offered, and the care they felt through the process. Over the last year, our team has hosted internal learning sessions to share and document our thoughts and reflections about the program design and process.

Applicants told us they valued the flexible budgeting, the support offered, and the care they felt through the process.

Some of these learnings include:

Clearer signaling on who the grant is for: Based on this pilot, we would also consider setting a clearer revenue cap for eligible groups and applicants to make it even clearer that this grant is for small-budget groups doing the critical, under-resourced work. We also continue to grapple with how to support small, meaningful initiatives doing important, underfunded migrant justice work while being embedded within quite large organizations that don’t have an explicit overall focus on migrant justice.

Accessible language and ways for applicants to express themselves: The application rubric, while thoughtful, still felt too jargon-heavy. We are also exploring ideas like simple narrative prompts in place of structured questions, and creating short videos or pre-application meetings to help demystify the process and build trust.

Providing personalized support, earlier: In our initial feedback survey, we received feedback that most applicants spent two to three hours on the application, while a few spent 10 or more hours despite our efforts to make the process lighter. This reinforces our commitment to reduce burden, save time for applicants, and deter them from feeling the need to overwork or over-wordsmith their submissions. This could be through an initial meeting between each prospective applicant and our team before applying to clarify expectations, offer tailored support, and help applicants determine fit before investing significant time. Despite offering application support, we noticed many applicants weren’t reaching out early enough or at all, suggesting we need even more proactive and creative trust-building outreach strategies.

Three persistent tensions we continue to hold

While we have always understood that doing this work well requires time, resources, and spaciousness, we are still learning how to name that openly and to treat it as a core part of the work, not just a background condition.

Throughout this process, there have been a few different tensions we continue to hold, balance, and sit with. Some of them include:

True cost of participatory design: One of our reflections during the application phase has been that stepping into the role of a funder — even within a participatory model — inherently comes with power dynamics that require more time and capacity to build good relations. From cultivating relationships with design group members, to holding space during community outreach, to supporting applicants and eventually grantees, this work requires deep relational labour. While we have always understood that doing this work well requires time, resources, and spaciousness, we are still learning how to name that openly and to treat it as a core part of the work, not just a background condition.

Limits of our capacity vs what we wanted to offer: We had hoped to offer individualized feedback or phone calls to every applicant who was not funded but quickly realized that this level of engagement was not possible with the main team members serving in part-time capacity on this initiative. With 142 applications and a six-member decision-making group, the process of compiling written feedback in a format that would be both accessible and meaningful proved untenable. While we considered sharing just the rubric scores, we recognized that, on their own, they wouldn’t offer much value or context. This remains a learning edge for us, one we hope to address more thoughtfully in the future.

Who finds us, who feels welcome, and who is left out: We see a growing number of funders move away from open applications, instead choosing to fund through deeper relationships and networks in the community, which is important and great for many contexts. While designing this process, the design group was mindful of the limitations of relying solely on our own networks, recognizing they carry unrecognized gaps and limitations, and don’t always reach everyone who should have access to funding especially in the context of under-resourced grassroots groups, some of which might not have received grants of any size before or even applied for one. Having an open application was one way to invite people beyond our circles and networks. This worked in many ways, yet we still sit with the tension: how do we ensure funding reaches the most impacted and not just those most comfortable applying? And how do we also ensure that we are not wasting the valuable, often underpaid or unpaid, time of community members doing critical work?

Looking ahead

As we look to the future, we are excited to build community with and to support the 16 grantees in other ways. This next phase is about walking alongside each initiative: through check-ins, grantee gatherings, and responsive support to emerging needs. We will be offering opportunities for collective learning around equity and solidarity, strategy and fundraising support, and amplifying their stories through our platforms. More than anything, we want this to be a journey rooted in care, co-creation, and mutual growth.

We are committed to keep reflecting, learning, and acting on community feedback to determine what needs to shift as we venture ahead. We are also in conversation with different funders to support future rounds of the grant and about what’s needed to sustain and deepen this kind of participatory grantmaking work. We know there’s more to do, and we welcome others to learn with us and share their learnings with us as we continue this work on collectively shifting power and building more just, caring, and equitable funding spaces.

Thank you to our partner:

This initiative is a result of a partnership between the RADIUS Refugee Livelihood Lab (RLL) and the World Education Services Mariam Assefa Fund (WES Mariam Assefa Fund).