A programmatic pause and re-emergence in times of suppression

By Yara Younis

In July, I shared a reflection piece on Indigenous-Palestinian existences, closing with an invitation for readers to “start knowing too”; the intent being to nurture imaginative futures in which we all want to stay stubbornly, spitefully alive. Where we all can dream and have space to be more than just alive in this world; where the default is not to diminish our right to existence but to embody being in our fullness.

This approach of embodying one’s fullness and creating spaces of life, — as coined by Queer-Trans Palestinian Yaffa AS— has been a core practice and value shared in the Migrant Systems Change Leadership Certificate program (MSCL), offered by our RADIUS Refugee Livelihood Lab (RLL), which I co-lead with a dream team. After offering the program every year from 2018 to 2021, our team decided to take a pause to recuperate and reflect on the experiences of past participants. We asked ourselves how the curriculum could respond to what we were seeing, hearing, and experiencing in our local and global communities.

Among all the richly diverse backgrounds of our participants, there was a shared experience, almost unspoken, of the pressure to “fit in” into what is deemed “Canadian culture” to be considered a “successful” newcomer.

During this pause, an observation persistently threaded itself through my thoughts: among all the richly diverse backgrounds of our participants, there was a shared experience, almost unspoken, of the pressure to “fit in” into what is deemed “Canadian culture” to be considered a “successful” newcomer. A Developmental Evaluation confirmed this observation. Over time, participants, supported by each other, began to recognize the inherent fallacy in this belief. The idea that a colonial system will treat you with dignity if you conform is an illusion repeatedly disproven by history. Dismantling these entrenched systems alone is nearly impossible, because they are designed to divide, individualize, and preoccupy.

Daily survival often leaves scant energy to demand systemic change from a settler colony designed to generate wealth for the ruling class. Shifts in federal immigration policies shape narratives blaming international students and temporary workers from so-called “third word” countries for infrastructural failures including healthcare, housing, and employment access. More so, these systemic dynamics take us further away from our knowing and from distinguishing truth and confusion in a muddled reality.

Our learnings, combined with rising systemic suppression, led our team to re-launch MSCL in September with the commitment of drawing out complexities of migrant spaces (rather than conformity). Together, we are sprinkling seeds of knowing on varying soil: not with guarantees or certainty of what will grow, but with hopefulness that another way of living is possible for all of us. In our space of life, knowledge is co-constructed; it is not hierarchical, discovered or found as the ultimate, singular truth. We are all knowledge holders and memory keepers of multiple truths and existences that colonial systems have tried to erase. And yet, the question remains: which knowledge is legitimized, and which are erased? By sharing space and experiences in a decolonial education setting, participants begin to see cracks in these systems and reject their own erasure.

In an era of rising anti-migrant rhetoric and diminishing funding for migrant-focused work, creating space is itself an act of resistance. Policies change, statements are made, but the tangible, lived challenges migrants face do not disappear simply because systems pretend they don’t exist.

Before we can engage in systems change in our MSCL sessions, we dedicate time to making space: to have space, create space, share space. Space as a verb becomes a practice, a material engagement. In an era of rising anti-migrant rhetoric and diminishing funding for migrant-focused work, creating space is itself an act of resistance. Policies change, statements are made, but the tangible, lived challenges migrants face do not disappear simply because systems pretend they don’t exist. In connecting erasure to the larger systems at play, I am often reminded of how fragile my belonging is, how disposable I am to these systems. If you know me well enough, you would know I have never been attached to living. Today, in light of ongoing Genocides (Turtle Island, Sudan, Palestine, etc.), I am staying alive to resist erasure. If anything, I sure am stubborn. MSCL, to me, is for those who feel there is no space for them, who want to inch closer into the realities of migrant existence under colonial systems and confront experiences they did not know were shaping us.

To navigate complexities of grief, exhaustion, the blurriness of time and the fogginess of my memory, while also carrying the collective entanglements of solidarity work, I gravitate towards authors and thinkers who articulate the emotions I hold but cannot name on my own. Recently, at a poetry book launch for Billy-Ray Belcourt’s An Idea of an Entire Life, a point about sentimentality and its necessity in staying alive resonated deeply: the acknowledgment of care, the insistence on feeling, and the naming of what is too often rendered invisible. I also cannot help but think of Refaat Alareer’s If I Must Die, a harrowing reminder that it is my responsibility to live.

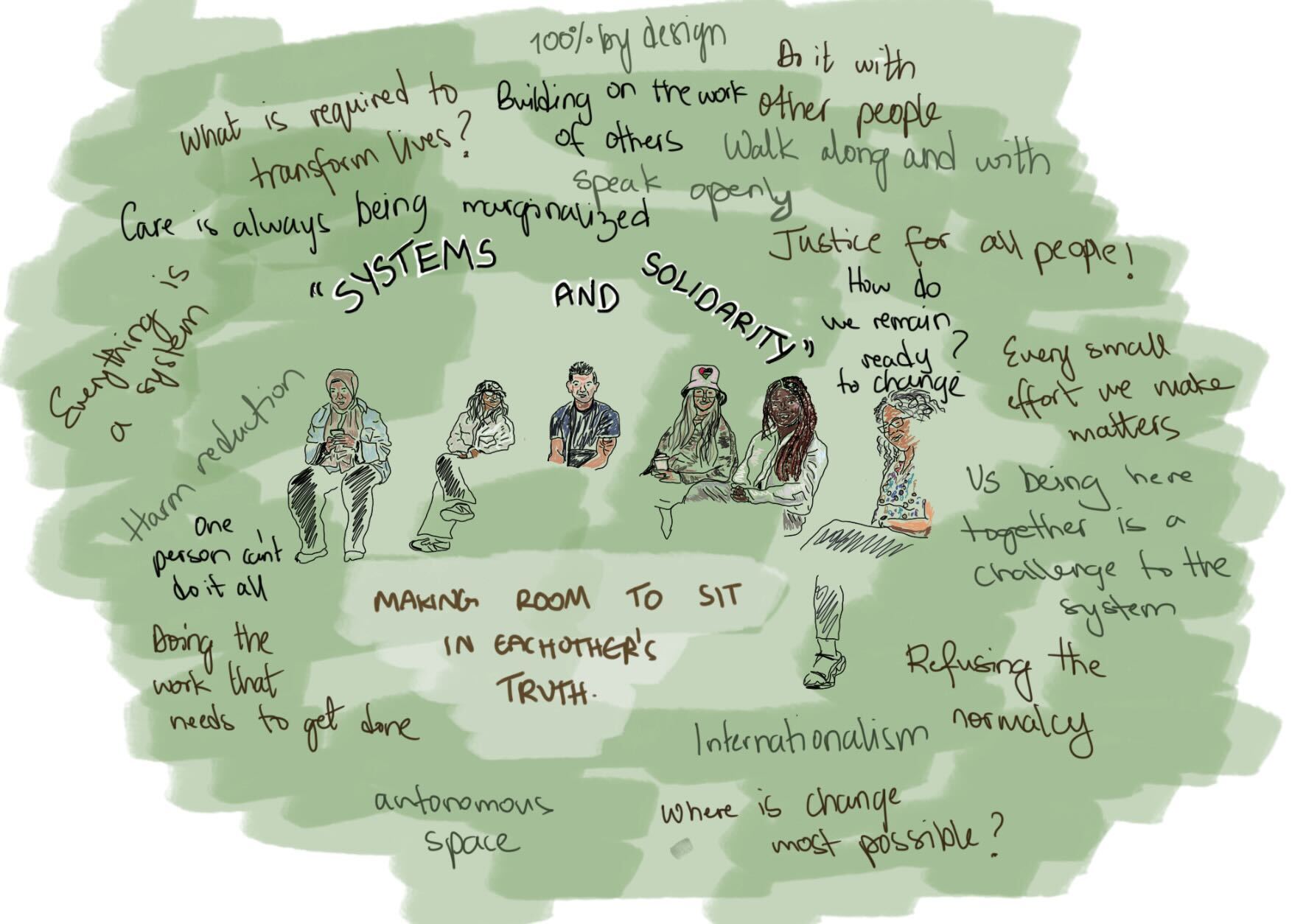

In that vein, I see this year’s re-launch of MSCL as an act of collective care and truth-telling; a commitment to support each other in staying alive for an expansive purpose. In that spirit, we opened the program with a community circle to explore “systems and solidarity.” Our truth-tellers, Diego, Aisha, Jada, Harsha, and Ingrid, moderated by Nada Elmasry, shared perspectives that resonate across daily practice: care is often marginalized, transformation requires collaboration, harm reduction matters, and no single person carries the energy to do it all, yet every small effort counts. We heard how autonomous spaces must be nurtured, how room must be made to sit in each other’s truths, and how work becomes sustainable when built collectively, on foundations laid decades ago. To walk alongside one another, to speak openly, to refuse the normalcy imposed by the system, and to remain ready for change, these are commitments as much as reflections.

That same afternoon, we were honored to share space with Jada-Gabrielle Pape, in an effort to deepen our cohort’s knowing of migrant-Indigenous solidarity.

We grappled with questions that unsettle and stretch us:

- What are the Indigenous truths we know?

- How much of our understanding is filtered through the State or colonial narratives?

- Where is our positional power, and how do we act responsibly with it?

A memorable highlight was learning that in Hul’qumi’num’, the phrase “Xwelmuxw Mestuyuxw” translates to “belongs to the Land people,” a reminder that the idea of ownership is not the default; stewardship and collective belonging are. We also reflected on “Nutsa’maat,” (one heart, one mind), and the importance of paddling together in the “canoe family,” not alone. A reminder that systems of colonialism and capitalism are intentionally designed to foster individualism and detachment from ancestral ways of being with life and land. This sentiment is further evidenced by the many newcomers who arrive with erasure or disdain for Indigenous peoples, unknowing yet shaped by systems (because, after all, none of us are exempt from systemic impact); our work is to interrupt this, to read, learn, and act on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 calls to action, and to consider where our positional power can contribute to justice for all Indigenous peoples on whose occupied lands we’ve settled in.

To inhabit a migrant space fully is to acknowledge both fragility and possibility, to stay stubbornly alive, and to cultivate connections that transform us and systems.

These reflections, from panels, workshops, shared spaces, and poetic resonances, all weave into the ongoing practice of making space for migrant life, knowledge, and solidarity. To inhabit a migrant space fully is to acknowledge both fragility and possibility, to stay stubbornly alive, and to cultivate connections that transform us and systems. The work is not linear, nor easy, but it is necessary. In the act of sharing space, of listening, of learning, and of doing together, we begin to inhabit a world in which we all have room to exist, fully and unapologetically, and from there, expand our capacities to imagine something different.

Thank you to Vancouver Foundation and WES Mariam Assefa Fund for making this space a possibility. To find out more about the Migrant Systems Change Leadership Program and how you can support spaces like this, please click here.