As an active guy with a background as a high-performance athlete and a career as a coach and in sports administration, Kabir Hosein understands intuitively how physical movement supports wellness. When he moved his family of six from Trinidad to Victoria, BC in 2019, he experienced first-hand the important role physical activity can play in supporting the settlement of newcomers and migrants. “Through my experiences of trying to navigate a very complex series of systems for me to move and enjoy myself, for my wife and kids to move and enjoy themselves, I could see an intervention was needed,” he shares.

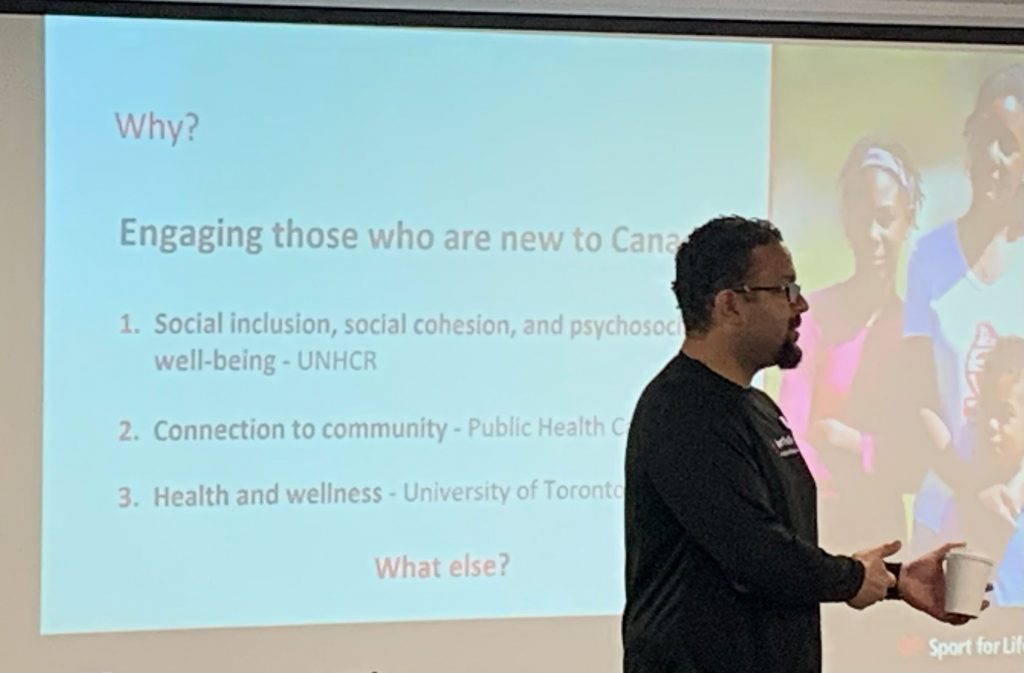

His position as an operations manager with the Sport for Life Society in Victoria, BC, put him in a unique position to make change. The organisation was already working to create equitable opportunities for participation in sport and physical activity. Kabir could see that he wouldn’t have to start from scratch: “It wasn’t me necessarily doing something new, but it was finding ways to change the existing system so that newcomers could flourish.”

When one of Kabir’s friends posted on LinkedIn about his certificate from the Refugee Livelihood Lab’s Migrant Systems Change Leadership program (MSCL) at RADIUS based out of Simon Fraser University, Kabir became curious about how the Lab might support him in his work. After learning more about the programs the Lab offered, he crafted his application, focusing on a project he could bring to life through his role at the Sport for Life Society. The project aimed to specifically support people who identified as being new to Canada and was called Wellness through Community Connections. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kabir was accepted into the 2022 online cohort for the Trampoline: Ideas into Action program.

During the program, he set to work designing an initiative that would support newcomers’ overall wellness through both structured and unstructured forms of physical activity. “Moving around at a playground, going on a walk or a hike, participating in shopping tours or museum tours, or even gardening counts,” Kabir explains. “Using these kinds of experiences to express your culture and build connection and understanding within the Canadian community you’re settling into could have a big impact on your body, mind, and soul — your whole life.”

From a tactical perspective, Trampoline equipped Kabir to understand some of the power dynamics that are present when engaging multiple sectors and stakeholders. To change the system, he saw that he would have to appeal to the various needs and wants of others connected with or adjacent to the programs he wanted to create. “Within the first few sessions of Trampoline,” he says, “I could see I was trying to do too much in one step and had to break it down. I thought I had a clearly defined project-management approach, but I needed to put a lot more detail and work into it.” Breaking it down included understanding the interests of the different stakeholder groups. “Recreation parks and trails in most cases are managed and coordinated by municipalities,” he explains. “Okay, so. What are their interests? What are the interests of the local sporting organisations?”

Through learning about liberatory design and systems thinking, conducting an environmental scan, and holding community conversations (a process in Trampoline that has participants seek feedback directly from community members), as well as having discussions with peers and program advisors, Kabir understood that “jumping in without proper understanding was why I had not been making much progress prior to attending the program.” He learned that many local sporting organisations, for example, want to increase membership, and most want to increase their diversity quota. A fraction of them, he says, “authentically want to be engaged and were willing to have the difficult conversations about what [things] needed to be changed and take the right steps to change them.” He points out that it’s not a one size fits all approach. “To disrupt the system,” he says, “I would have to appeal to what would motivate more of these various stakeholders to want to have these conversations in the first place, so that they could in turn buy in and then change the way that they have been doing things.”

Being relatively new to Victoria, it was in doing this preparation, as prescribed by the Lab, that Kabir fully grasped — and developed a nuanced appreciation for — the geographic region he was working in. “There’s a difference between greater Victoria and the Capital Regional District,” he explains. “Victoria has 14 municipalities, eight towns, and four hamlets, and I found out that matters because I went about doing the environmental scan. I learned slowly how to go about doing my research, who to ask, what questions to ask, and when the right time to ask the questions was.”

A key benefit of participating in Trampoline, says Kabir, was “being continuously motivated, especially when there were times where I felt like I was hitting brick walls.” With the support of the Lab facilitators and the cohort around him, he was encouraged to keep pushing forward: “I could see the work that I do today would benefit my kids and their kids and other people and their families, too, and so forth.”

Each weekly session had a predictable delivery model where the Lab facilitators shared some content: a tool, framework, or concept-in-theory the group would be invited to reflect on individually before working through it or discussing it together. Having the “space to play around with the information” helped it marinate, and Kabir reflects that as participants were sharing their experiences within the cohort, “it seemed like each person was having similar challenges in a different way.” Kabir says, “I saw similarities in the ways they went about navigating things with some of the ways in which I navigated some of the challenges. We were helping each other in a community of practice, and it felt good to be a part of it.” The round table with program mentors, which took place about halfway through the program, was yet another chance for feedback. “Some of the mentors were graduates of the Lab, and they were actually doing this work and living it,” Kabir recalls. “They had the experience of how they applied that systems-change approach, and we had an opportunity to present what we were doing and then learn from what they did. It was really helpful.”

The project Kabir brought to Trampoline, Wellness through Community Connections, is still operational today through the Sport for Life Society and is really making a difference by creating opportunities for newcomers to build resilience through connection in their communities. “I had the opportunity to use the adapted approach, based on the learnings from Trampoline, to create proposals for programs in other communities that successfully gained funding,” he explains. “So, it’s no longer just in Victoria, it’s in Surrey, Northern BC, Prince George. We are currently consultants for three National Sport Organizations (Squash, Table Tennis and Soccer) with regards to the EDI initiatives, and as an organisation, we have ongoing projects in Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, Winnipeg, and a number of other cities or communities that are able now to apply their learnings and gain the support of their stakeholders. It’s really kicked off. But there are also lots of offshoots where I created a pathway for the project and then I integrated the project into existing initiatives of the organisation. And that’s expanding now, too.”

In fact, Kabir has been promoted within the Sport for Life Society not just once (into the Senior Manager position), but twice since attending Trampoline, and he currently serves as the organisation’s Director of Strategic Initiatives. “I actually started implementing a project which gave rise to growth and expansion from a revenue standpoint, from networking and partnerships perspectives as well,” he says. Within the national reach of his director role, he leads not only this project and others like it, but also the engagement for equity-deserving groups. “In addition to a full newcomer programming unit, we now also have an Indigenous Initiatives unit, led by Mataya Jim, that supports physical activity and wellness in the Indigenous community,” he says. “We have projects developing around supporting girls and women with the intersectionality of how they identify. We have programs for low-income families. There is lots in development.”

Kabir’s smile as he shares what Sport for Life has been able to achieve shows how passionate he is about the work he’s doing and how inspired he is by the potential systems implications of holistic physical activity programs. The smile fades a little when he shares a few of the pressure points he contends with, including introducing the potential for programming in places where Sport for Life does not have a physical presence, or in instances where dynamics between community stakeholders or potential partners might be unique and therefore considered not suitable for replicating or adapting an existing framework. “I have learned,” says Kabir, “to move from collaborating to co-creating. We are each on a journey, and when the universe brings us together, that is when the magic happens. So, I am learning from the tortoise to be slow and steady now.”

Accessing funding — and the evaluation required to report on that funding — also presents a significant obstacle. “Often, traditional funders, they like to have an academic institution attached to the evaluation of the initiative,” Kabir explains. “This requires ethics approval, and then the language that is used is actually very confusing for the actual racialised newcomer that we want to be able to understand what we did and how it changed — or didn’t change — the system. I feel like I’m being boxed into that academic space. We almost have to lobby the traditional funders to help them understand that we can’t be boxed into their intended outcomes. When we co-create an approach that hasn’t been done before, and start doing the activity, we need to be consistently responsive to what’s happening. Sometimes we learn that we’re having different outcomes that are more meaningful to the community we’re trying to serve.”

Despite the challenges, Kabir is motivated to do what he can to advance the impact that the Sport for Life Society has with newcomers and other equity-deserving communities, and not get bogged down by things that are beyond reach. “These initiatives could actually create generational changes,” he says. “This work takes time, and we are gradually moving things forward. As Canada recruits close to a million newcomers by 2030, this presents a beautiful opportunity to use sport and physical activity to foster a sense of belonging.” Since participating in Trampoline, Kabir has continued to be connected to and motivated by members of the Lab community, including participants, mentors, and Lab facilitators. Whether it is a sense of connection he feels more broadly when the group shares events, opportunities, and support through their WhatsApp channel, or the handful of closer ties that have led to co-creation and networking opportunities, Kabir says he feels grateful to be part of a remarkable community. “I feel comfortable that whenever there’s a need, if I reach out, I’d be supported,” he says. “I know I have the opportunity to pop into the Lab when I’m in town. I can use it as a meeting space. I know there’s also opportunity to potentially partner with the Lab or others in the network to do systems-change work in the future.”

The Refugee Livelihood Lab is part of a growing movement supporting deep shifts in the systems which govern our lives towards equity, dignity, and sustainability for all people and the planet.

Thank you to our funders Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction, and WES Mariam Assefa Fund (MAF).